A horizontal window looks the way it sounds — a ribbon of transparent glass spanning the wall of a building. While a vertical window frames a full slice of outdoor strata — grass, pavement, buildings, sky — a horizontal window reveals only the upper layers, in a panorama disconnected from the ground.

The horizontal window appears as a principle of modern architecture in Le Corbusier’s 1926 manifesto, Five Points of Architecture [Les cinq points d’une architecture nouvelle], which shaped new construction in and beyond Central Europe. The 1930s-40s in Hungary, for instance, saw architects who read or studied under Le Corbusier erect modern buildings that bore his influence. Vera Molnár, one of my favorite early computer artists, began studying in Budapest around this time, in 1942, at the Hungarian University of Fine Arts.

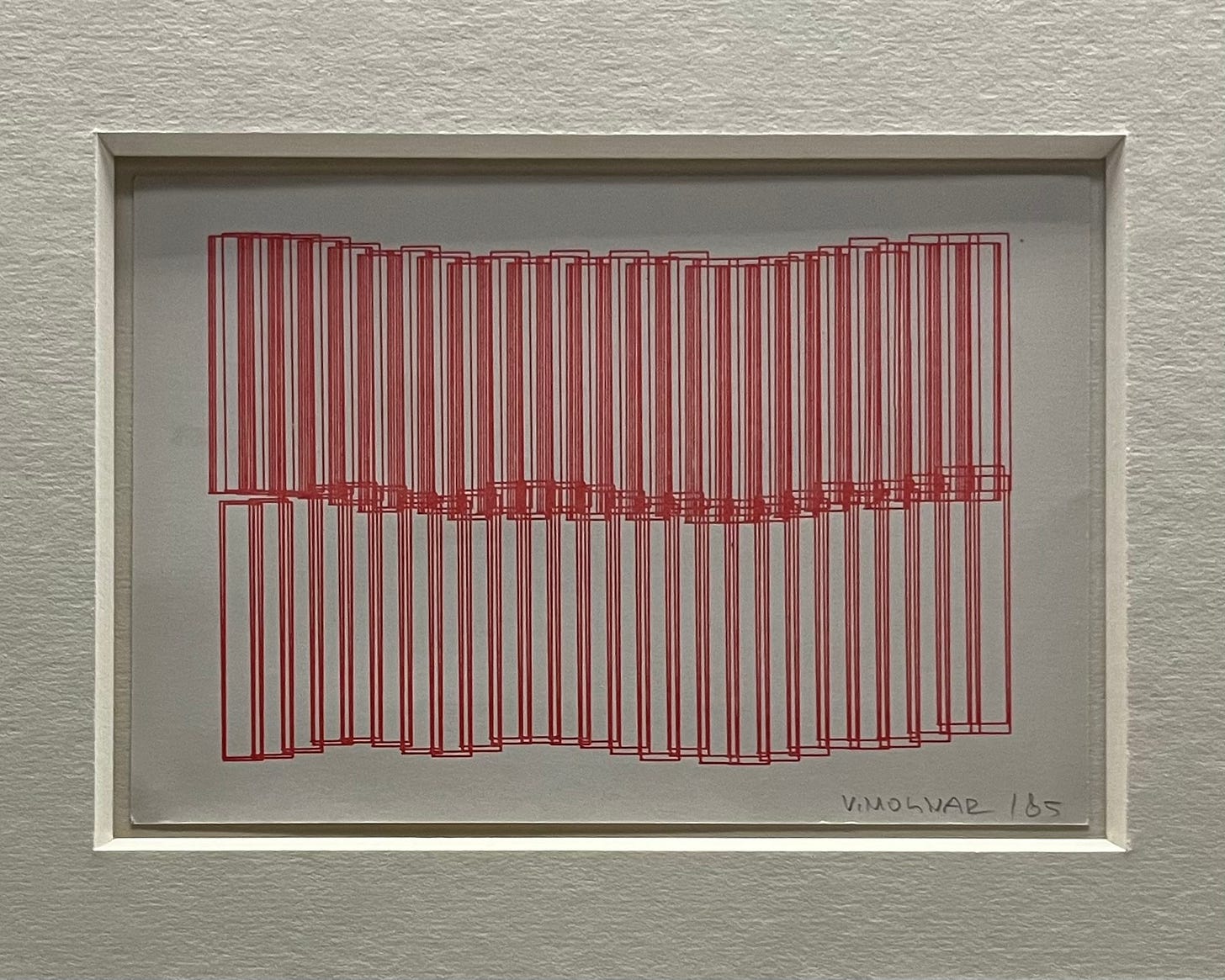

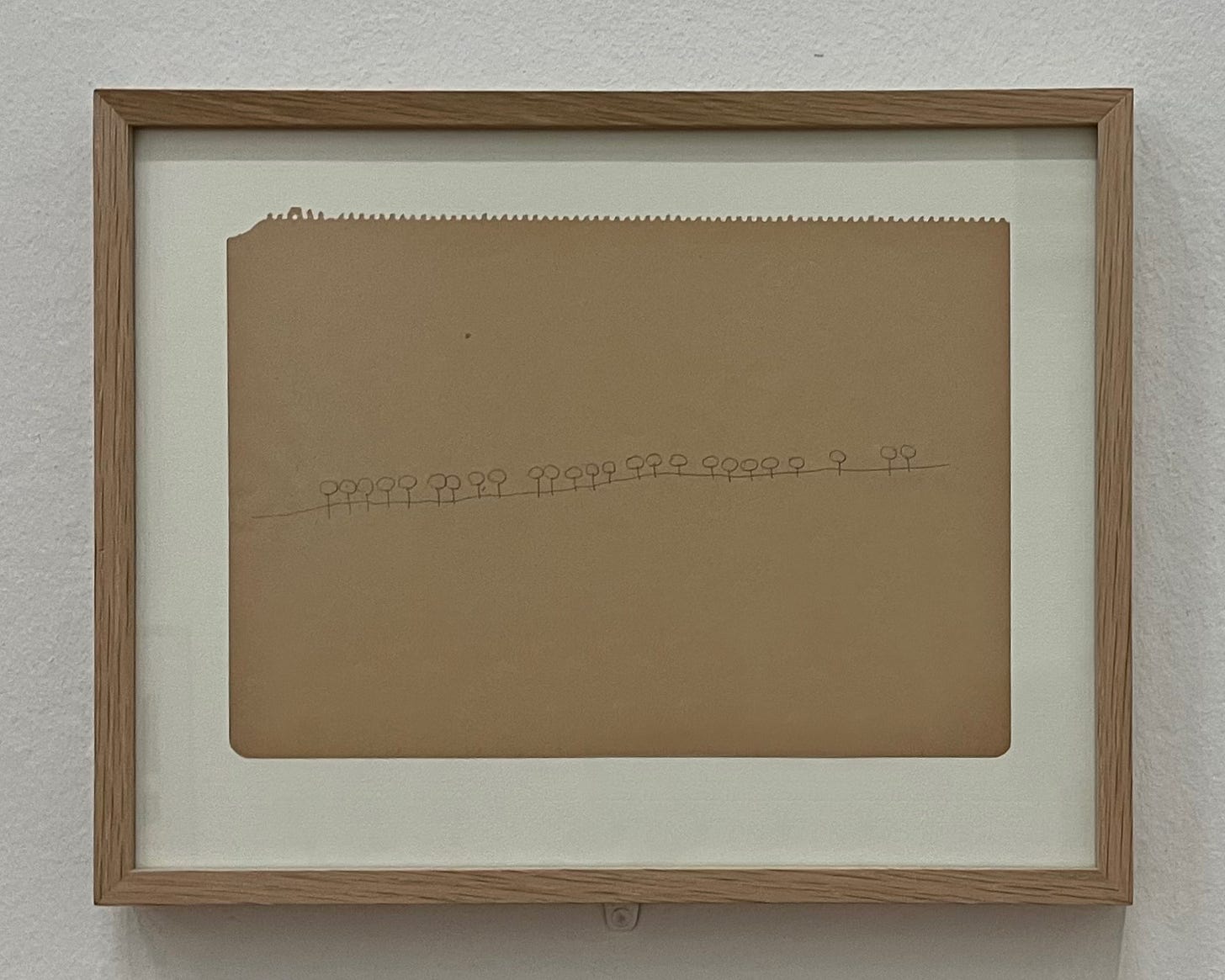

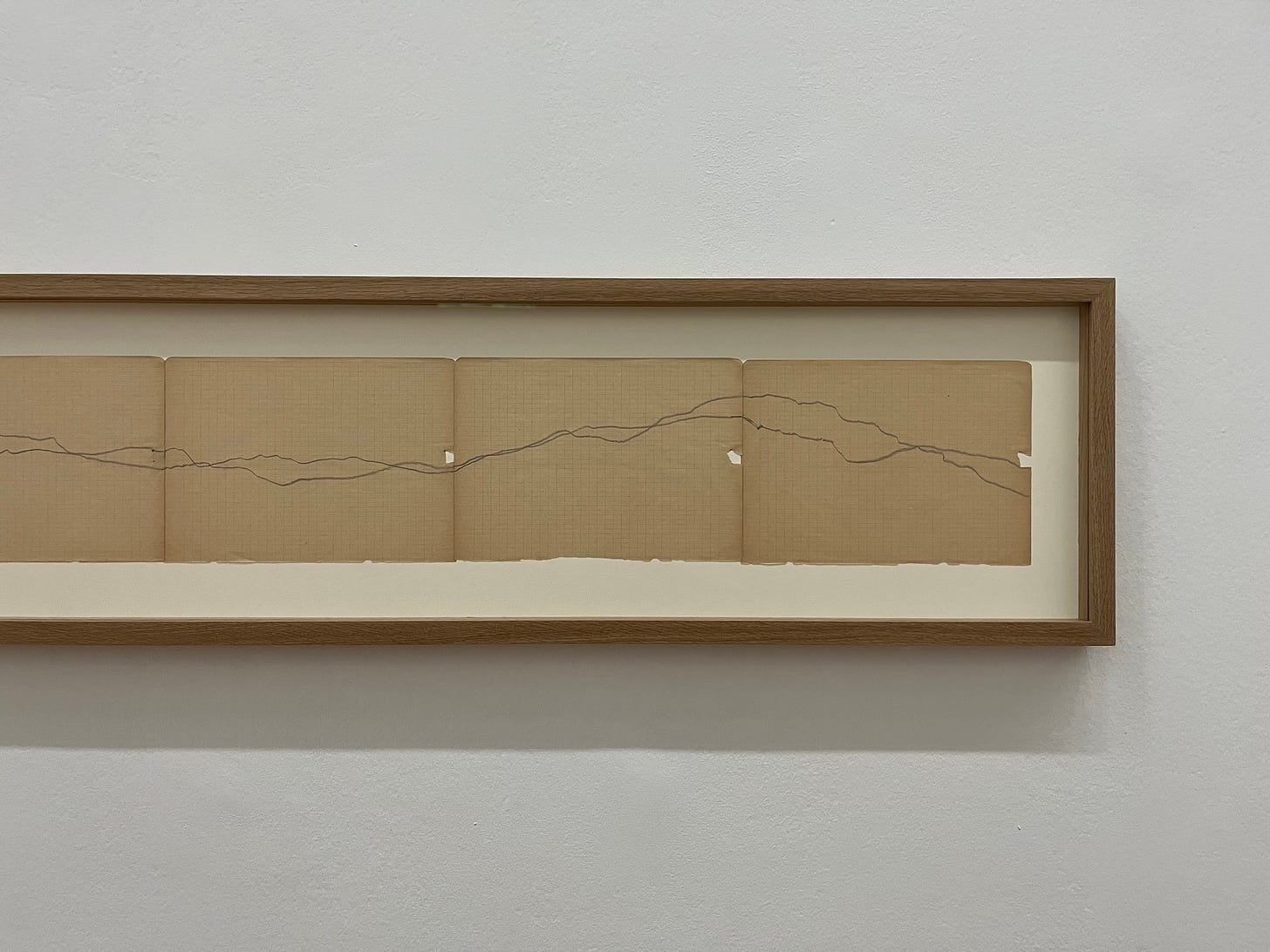

Molnár is best known for her abstract compositions that procedurally transform geometric shapes. The Centre Pompidou in Paris recently held a retrospective honoring her life and work, and among many wonderful pieces, I saw for the first time her Geometric Trees and Hills [Arbres et collines géométriques] (1946), a series of early drawings on brown sketch paper.

The drawings are striking in their austerity. Flat and spare, they simplify the Transdanubian landscape of Molnár’s childhood into basic circles and lines. Contextual elements are absent — no villages, no lakes, no sun, no clouds. One drawing depicts lollipop trees dotting a horizon, like points on a wobbly x-axis.

Another is a bare mountain ridge spanning panels of graph paper. Both drawings have a displaced panoramic perspective with a floating horizon, similar to that of Le Corbusier’s horizontal window, which we can see in a view of the Swiss Alps from one of the architect’s villas.

Architectural ideas have the potential to open up new ways of seeing. Could modern affordances in the built environment of Budapest have inflected Molnár’s abstract landscapes?

Molnár herself does not know what to make of these trees and hills, but believes they prefigure her whole body of work. “Looking at these drawings,” she says, “I have the impression that everything I've done since then stems directly from these few sketches.”

(For more on the simplified Hungarian landscape, see Maps that map themselves.)