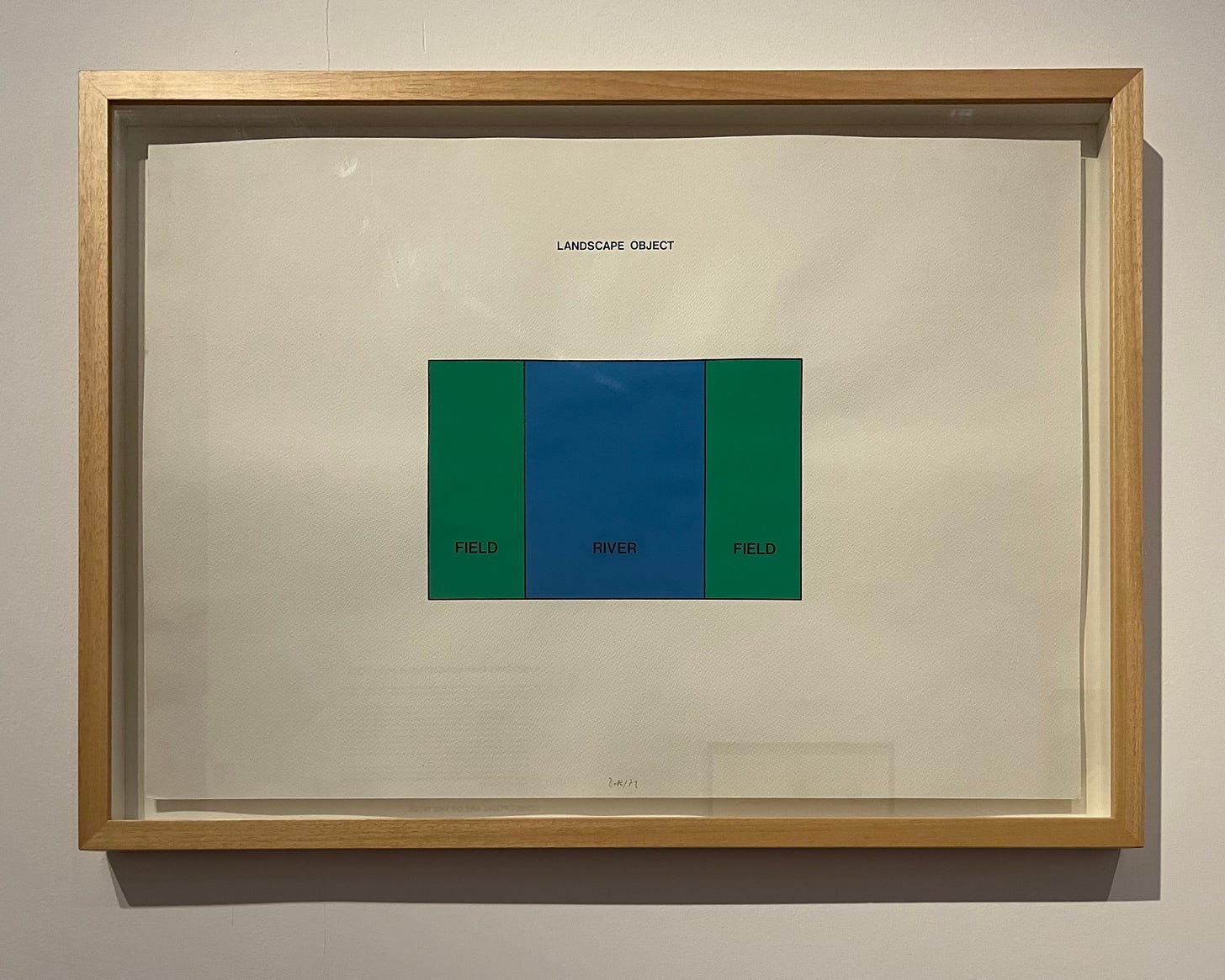

I came across Landscape Object by Imre Bak at the Hungarian National Gallery in Budapest. The work is unapologetically plain, comprised of three rectangles under the words LANDSCAPE OBJECT — one blue, labeled RIVER, and two green, labeled FIELD. The rest of the paper is blank.

One response to this piece is to try to reconcile it with the physical world. As Bak worked in Budapest, the Danube seems like an obvious reference, with Buda and Pest as the green fields on either side. But Landscape Object names no specific river, and provides no scale. The composition is so abstract that it could represent any river on earth.

Bak’s piece is reminiscent in its absurdist universality to the “Map of the Red Sea,” below, from humorist Oliver Herford’s offbeat — and poorly-aged — atlas, The Simple Jography, or How to Know the Earth and Why it Spins:

The Red Sea here is a wash of red ink, which puns on the one between West Asia and Africa. Tautological accuracy, along with unverifiable correspondence to the physical world, is the punchline.

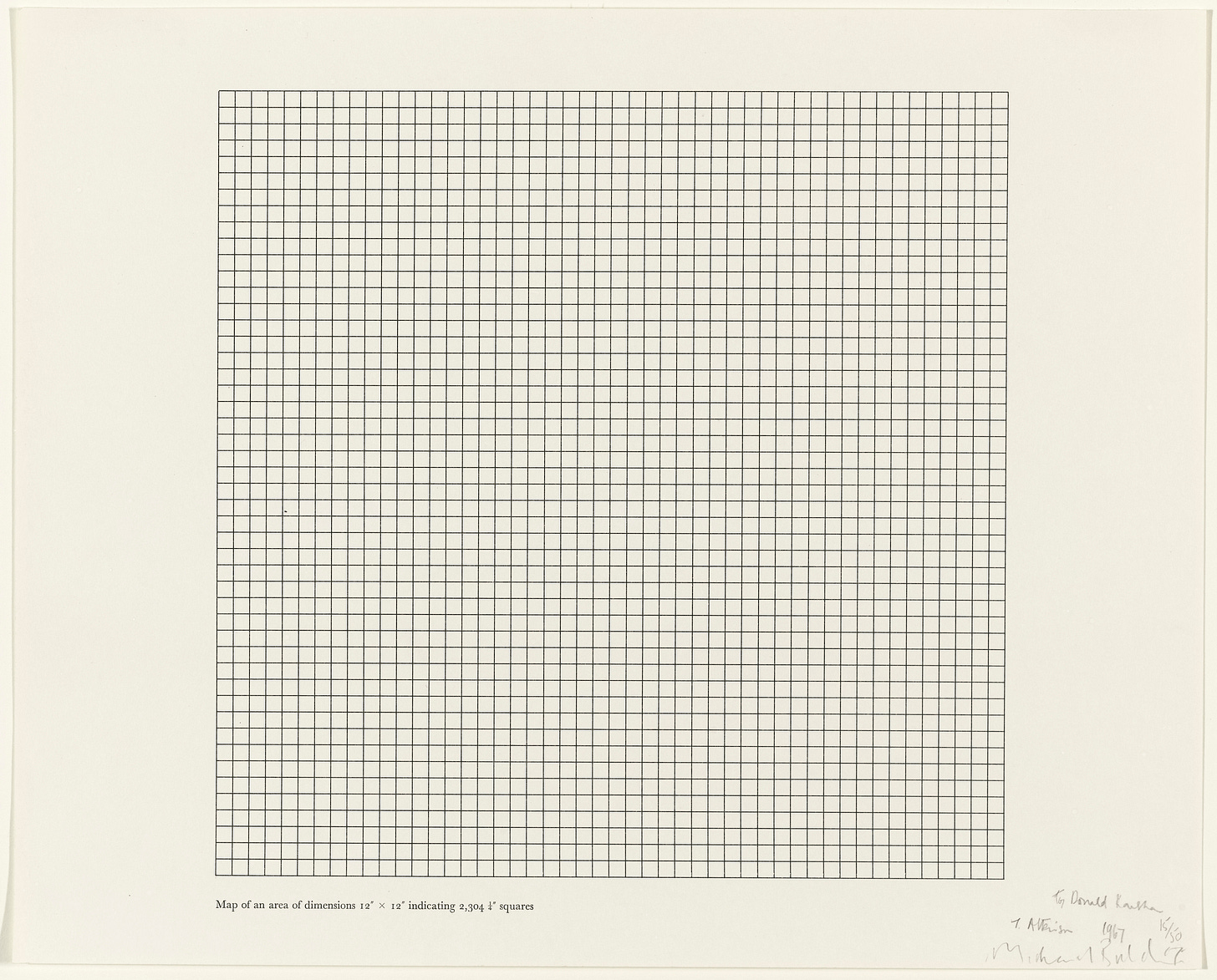

Art & Language, an English conceptual art collective founded in the 60s, produced several works riffing on the relationship between the map and the territory. The piece below, Map of an Area of Dimensions 12" x 12" Indicating 2,304 1/4" Squares (Map of Itself), “maps” a purely graphical expanse of grid cells.

Conventionally, the purpose of a map is to represent a physical territory. For each of these representations, the graphic is the territory. Entirely self-defined, purely self-referential. The outside world doesn’t have to exist for any of them to be true.

Which, formally speaking, is the case for any map.